Welcome back! Wow. Last week’s blog on Heroin vs Prescription Opioids really hit a nerve for a lot of our readers. We hope that moving forward the conversation can take on a new vibe and all patients are considered, rather than just those who would become addicted. If you missed this blog and would like to catch up, click HERE.

This week, we are going to examine the concept of trauma. What it is, what causes it, and how it informs our behaviors.

The year was 1990. The last sound I heard was what I perceived to be an explosion (it was actually a semi truck hitting the car behind me). The next five years were filled with all the things that go along with a traumatic brain injury. My job was to recover. Nothing more. The day I called social security and informed them that I had a job and would no longer be needing their services was the day my life began again.

It’s been almost 30 years, and I still startle when I hear an unexpected loud noise. Two box cars banging together on a train track can send me to the floor of my car, “waking up” two hours later, unaware of what just happened. Fireworks after the 4th of July, on a hot August night, can cause me to sit up in bed, heart racing, sleep out of the question for hours, my brain unable to untangle the idea that fireworks don’t just happen on the 4th.

So if I recovered from my brain injury, and have resumed a good life, why do these things keep happening? One word. Trauma.

My trauma was, in my opinion, mild compared to someone who has been the victim of a sexual assault, human trafficking, gun violence, or combat. The interesting thing about trauma? It doesn’t care. All events record the same. The healing depends on the severity of the impact (this varies from person to person) and the ability to seek treatment.

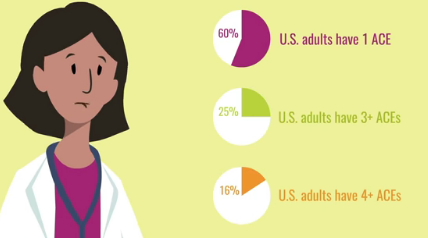

The most noted trauma that many people don’t think about, is that when we are young. According to Psychology Today, “Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Kaiser Permanente, assessed associations between childhood trauma, stress, and maltreatment, and health and well-being later in life. Almost two-thirds of the participants (both men and women) reported at least one childhood experience of physical or sexual abuse, neglect, or family dysfunction, and more than one of five reported three or more such experiences

“A woman’s experience of trauma impacts every area of functioning, including physical, mental, behavioral, and social. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health, 55 percent to 99 percent of women in substance use treatment and 85 percent to 95 percent of women in the public mental health system report a history of trauma, with the abuse most commonly having occurred in childhood.

“Women were significantly more likely than men to report more traumatic experiences in childhood. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) scores were found to be highly correlated with serious emotional problems, health risk behaviors, social problems, adult disease and disability, mortality, high health care and other costs, and worker performance problems.

“Higher scores were also significantly correlated with liver disease, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, heart disease, autoimmune disease, lung cancer, depression, attempted suicide, hallucinations, the use of antipsychotic medications, the abuse of substances, multiple sex partners, and an increased likelihood of becoming a victim of sexual assault or domestic violence.”

Take away message: the younger you are when you experience trauma, the more likely you will be at risk for health issues and more trauma later in life. That’s huge.

So what is trauma? What happens in our brain when we experience trauma? I’m glad you asked.

J. Douglas Bremner, MD states, “PTSD is characterized by specific symptoms, including intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, flashbacks, nightmares, and sleep disturbances, changes in memory and concentration, and startle responses. Symptoms of PTSD are hypothesized to represent the behavioral manifestation of stress-induced changes in brain structure and function. Stress results in acute and chronic changes in neurochemical systems and specific brain regions, which result in longterm changes in brain ‘circuits’, involved in the stress response. Brain regions that are felt to play an important role in PTSD include hippocampus, amygdala, and medial prefrontal cortex. Cortisol and norepinephrine are two neurochemical systems that are critical in the stress response“.

To paraphrase neuroscientist David Eagleman in his fascinating book, Incognito, the Secret Lives of the Brain, “there are as many connections in a single cubic centimeter of brain tissue as there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy!” This makes the brain the most complex organ in the known universe and helps us understand why such all-encompassing problems such as PTSD can become deeply embedded in our brain and subsequently our psyche.

The brain is so fascinating and when it comes to recording trauma, it is now believed that the person who experienced the trauma, will not be the only one to experience PTSD.

“Research is suggesting that unresolved PTSD can facilitate lasting physiological changes and that these modifications can be passed on to the next generation.”

-Dr. Schwartz

Generational trauma. How is this possible? Dr. Arielle Schwartz gives us our answers:

- “Environment: Parents with PTSD respond differently to their children resulting in greater disruptions in care and attachment. Mothers with PTSD are more likely to be both overprotective and reactive and as a result children may develop less-secure attachment.

- “In Utero Influence: Research has been following the infants born to mothers who were pregnant and diagnosed with PTSD after the 9/11 attacks to the world trade center. Studies suggest that these infants were exposed to maternal PTSD related cortisol changes (A review of this research here). As a result, the infants had low birth weight and revealed decreased levels of bloodstream cortisol when compared to a normative group.

- “Epigenetic: Studies of 2nd generation children of holocaust survivors reveal that children of mothers with PTSD are more likely to develop PTSD as differentiated from children whose father’s had PTSD suggesting the possible influence of genetics as differentiated from environmental influence. Twin studies also reveal a greater prevalence of PTSD among trauma survivors who also had a twin with PTSD further reinforcing a genetic model. While more research is needed to tease apart the nature vs. nurture debate, results strongly suggest that there may be an epigenetic component to the transgenerational transmission of trauma.”

So why is this information so important? Because treatment for people who have experienced trauma will be different than treatment for people who have not. Untreated PTSD can have life long consequences to our mental and physical health. It’s important to get treatment and that treatment is different for everyone.

Trauma Informed Care (TIC) is discussed in a paper written by Angelina Pelletier, MS, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Department of Psychology: “Mental health professionals need to pay attention to the role that traumatic experiences play in their clients’ lives, as well as the need for trauma-informed interventions”.

The Trauma Informed Care approach tells us that, “Four dimensions of recovery have been identified; these include health, or the ability to

overcome and manage ones’ disease and live in an emotionally and physically healthy manner; home, including finding a safe and stable place to live; purpose, which includes the ability to engage in meaningful daily activities; and community, which includes relationships and social

networks that provide the individual with support, friendship, hope, and love (SAMHSA, 2014).

“There are also several key concepts that are important to the recovery movement. These concepts are empowerment, self-determination, and the importance of the individual wellness experience (Scheyett et al., 2013).

“Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) is an approach, similar to recovery, which allows both the mental health professional and the client to address the impact and treatment of trauma for individuals. Individuals who do not adequately address the role that trauma has played in their lives are often less likely to experience recovery in the long-run (SAMHSA, 2014)“.

This video is a “must see” for anyone who provides care. It brings this model into focus. If someone you know, has experienced trauma and has lasting effects from it, please share this blog with them. There is help available. Life can find a new normal and a new balance.

1 Comment